“The sourball of every revolution: after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?”

Maintenance Art Manifesto, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, 1969

"Previously built architecture is a maintenance issue more than anything else."

Gordon Matta-Clark, interview with Donald Wall, 1975, Canadian Centre for Architecture Archive

A few weeks ago, during his Basketball Hall of Fame Enshrinement speech basketball player Dino Radja thanked, among the others who contributed to his successful career, “all cleaning ladies” after which the audience chuckled. The chuckles in the audience showed how the work of maintaining, “making sure this object or entity or relation is enabled to continue existing over time, despite time's ravages on its existence and persistence”1 is still underappreciated and misunderstood. Not seen as a part of a creation, or heroic production, it is seen as an afterthought, a nuisance resembling the hangover after a really good party. Management, while maintaining a slightly better reputation because of its association with an immaterial, cognitive labour, still suffers from being perceived as boring, as it “is not the modality of creating, inventing, producing anything but guiding, organizing and optimising the activity of others.”2

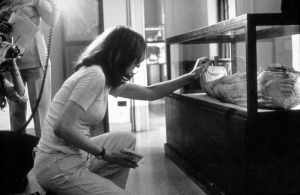

Yet, maintenance and management, while enabling, determine how a building is used and what is possible in the building. How should the fire escape be marked? How much weight can be placed on a floor? What is the largest object that can pass through the door? Who can clean the exhibition space, and how often? Who can sweep the floor around exhibited artefacts? And who can dust the artefact itself, and how? All these questions, mundane at first glance, become of the utmost importance at the very moment the building is completed and transitions from the mode of construction into a mode of exploitation.

During this course we will look at how protocols of maintenance and management influence what can be done in and around the Kunsthaus Graz – understanding that exceptional architecture sometimes requires exceptional routines – what keeps it alive? We will look for and try to make visible the invisible protocols of management and maintenance which regulate what can and cannot be done in the Kunsthaus Graz; what kind of artistic intervention is possible or impossible due to limitations placed on the space by fire safety, security, cleaning, and other protocols, remembering that “maintenance is not a separate process to be juxtaposed with the finished building; it is a constant act of becoming that necessarily relates to the architectural object. Architecture and maintenance are inherently interdependent.”3

During this course we will use maintenance and management as optical machinery, as a way of seeing the world, to understand how their respective protocols shape what is possible and what is not possible in the space. Using observation and interviews, as well as drawings and photography, as tools of investigation in the first part of semester, we will build an individual and collective body of knowledge – which will be translated into an exhibiting project exposing how invisible protocols of maintenance and management shape space.

1 Vishmidt, Marina. ‘Management and Maintenance’. In Look at Hazards, Look at Losses, edited by Anthony Iles, Danny Hayward, Marina Vishmidt, new media center_kuda.org, and Group for Conceptual Politics. London: Mute Books, 2017 p. 12

2 ibid.

3 Sample, Hilary. 2016. Maintenance Architecture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. p.100