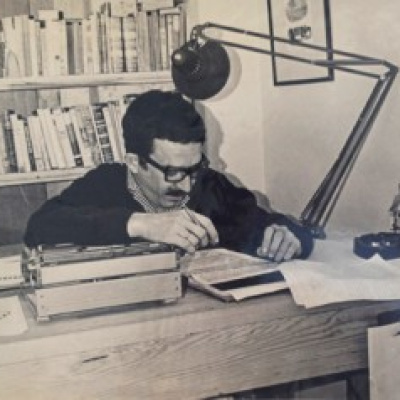

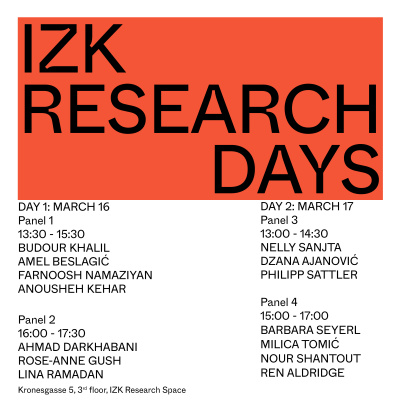

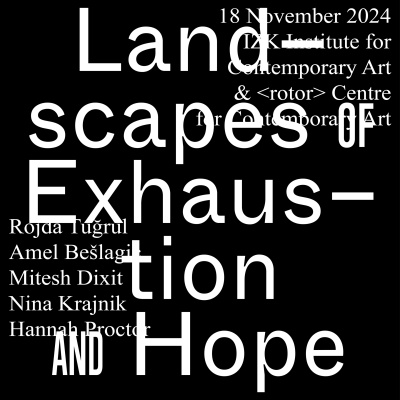

Abdelrahman Elbashir, Budour Khalil and Anastasiia Kutsova

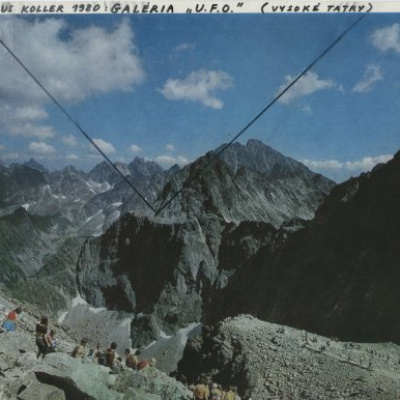

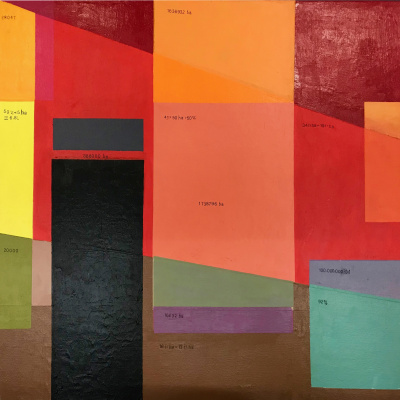

Part of the Land, Property, and Commons exhibition in Semmering curated by Hedwig Saxenhuber with the work Flowers (Not) Worthy of Paradise by Milica Tomić

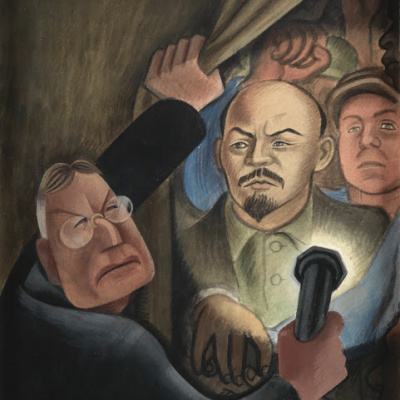

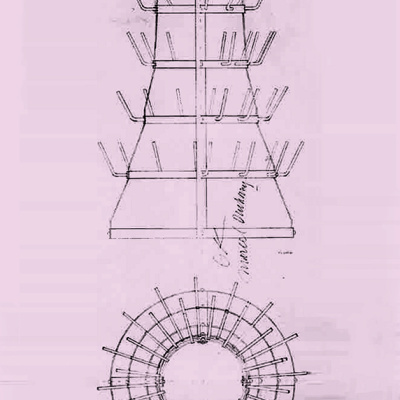

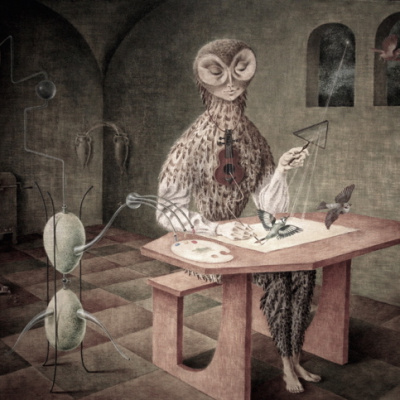

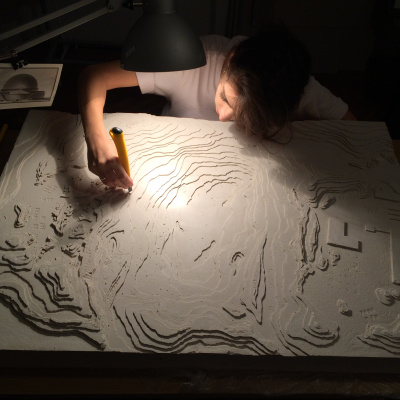

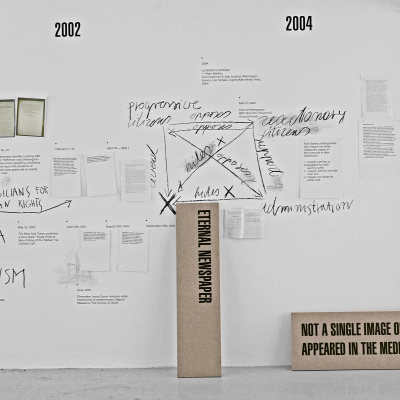

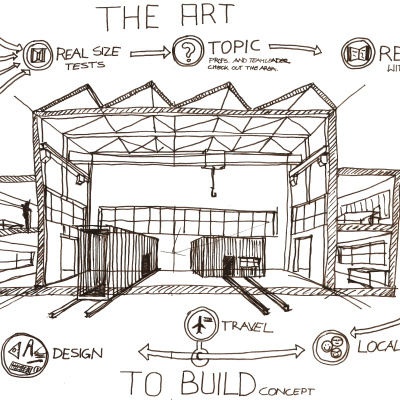

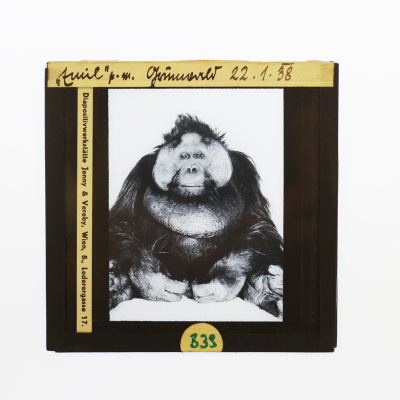

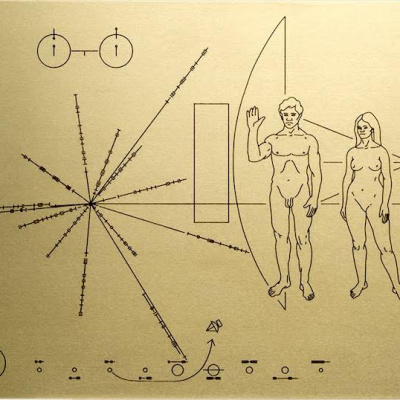

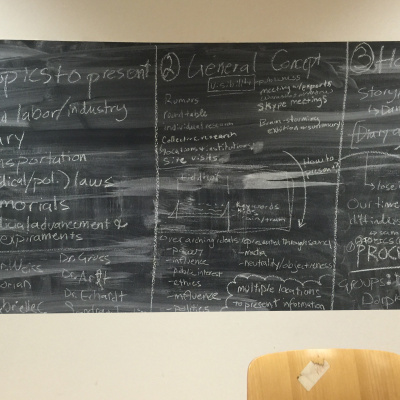

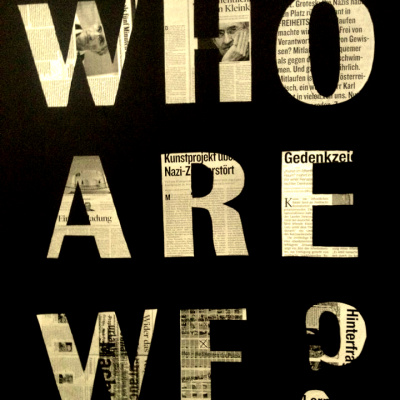

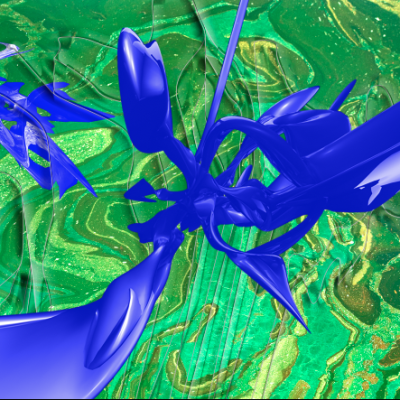

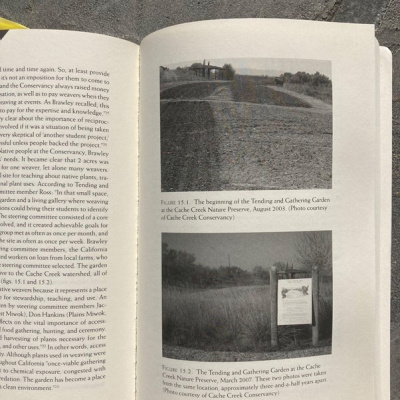

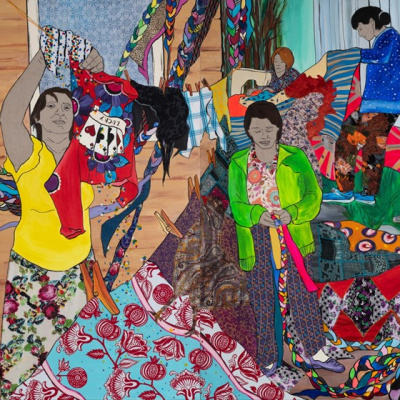

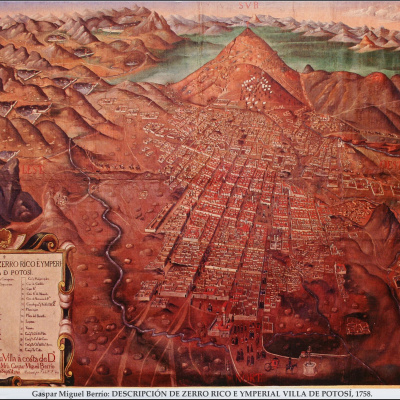

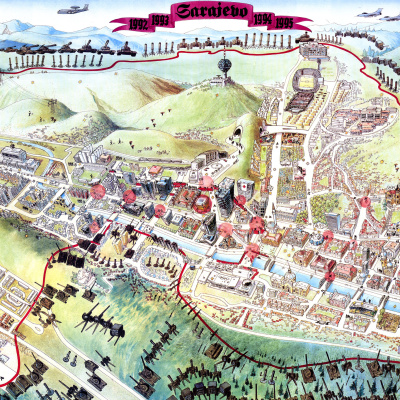

If the sublime landscape of Semmering and its history can be seen as a backdrop, a set for the theater of societal hierarchies (Sekulić and Tomić, 2020), Milica Tomić asks whose labour is exploited to maintain them as sites of nourishment and enjoyment; who is displaced and whose land is occupied? Who are those who remain cast out of the “Euro-Christian garden of ‘earthly delights’, even if it is precisely their knowledge and labour in the real garden that feeds and sustains this symbolic garden.” (Gray and Sheikh, 2018) Tomić invites students (IZK, Architecture faculty, TU Graz) to look for different forms of knowledge and relations that counter the representative, imperial Landscapesthat feature so prominently in the Western imagination. In her installation, Tomić looks at the garden as a form of resilience and resistance to colonial barbarism and forced acculturation. Anastasiia Kutsova draws attention to the ЖКХ (ZHKH) garden art that features various aspects of Ukrainian post-Soviet realities and seeks for new societal forms. Abdelrahman Elbashir’s research unpacks the materialised emergence of the political from the agricultural landscape in contemporary Sudan through histories of relational systems in the context of British occupational rule.

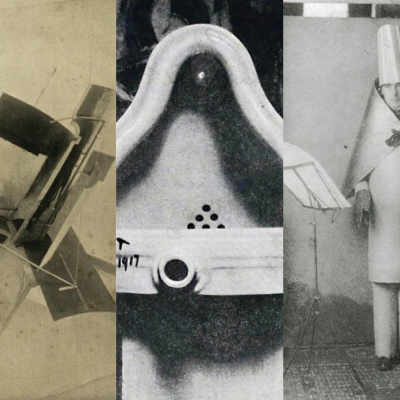

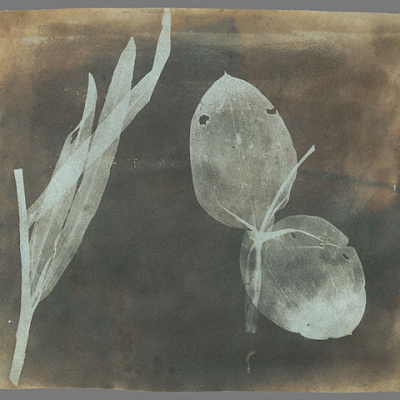

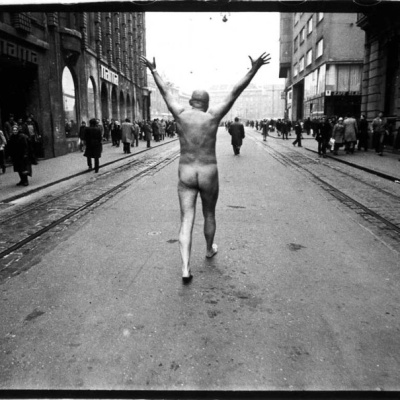

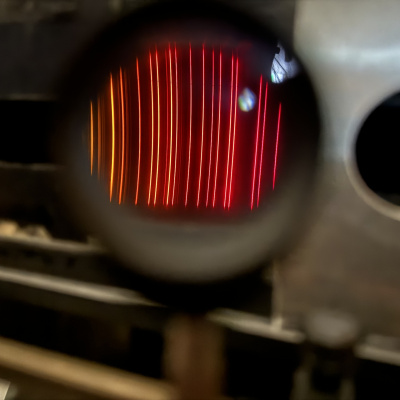

Shutter

Budour Khalil

‘’Paralleling this mass of water, the third metamorphosis of the abyss thus projects a reverse image of aIl that had been left behind, not to be regained for generations except more and more threadbare in the blue savannas of memory or imagination.’’

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation

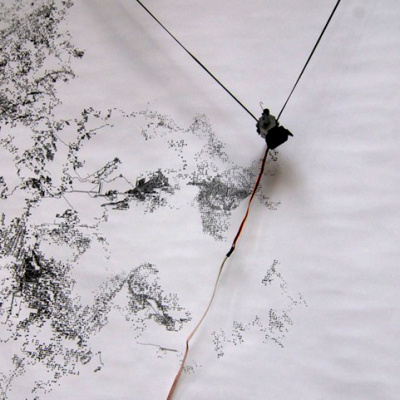

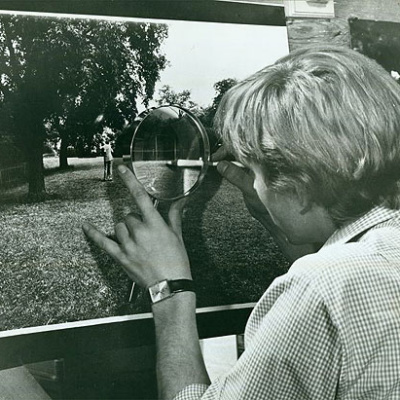

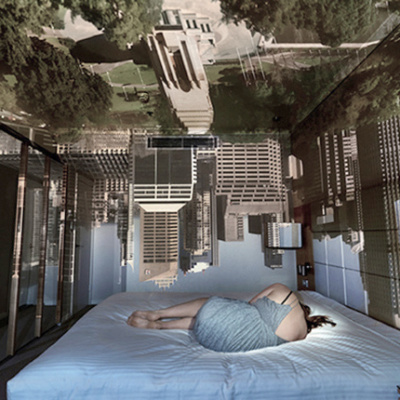

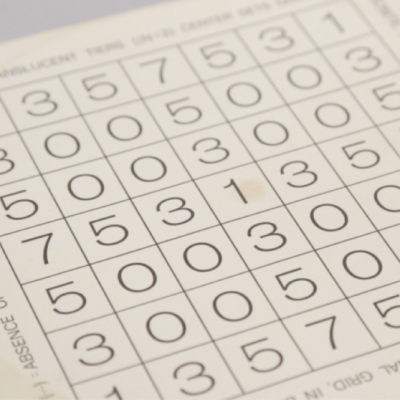

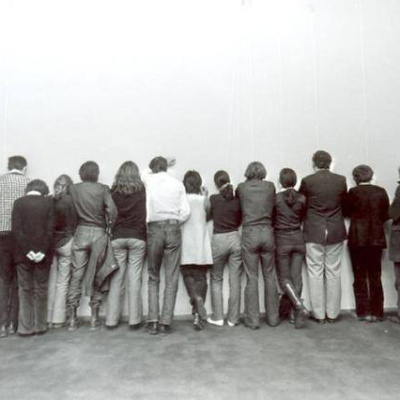

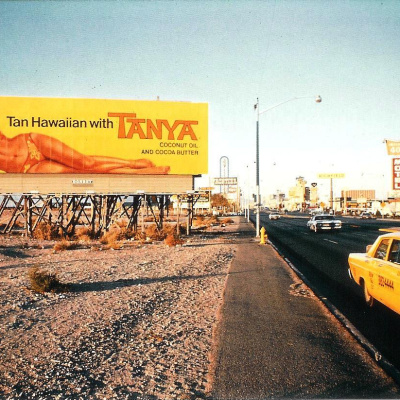

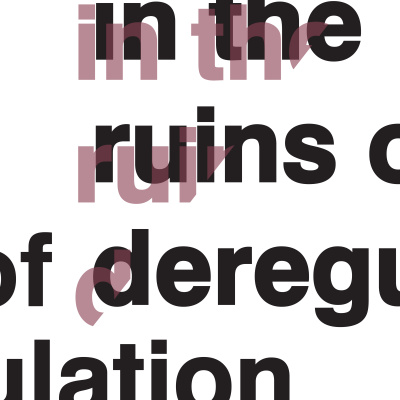

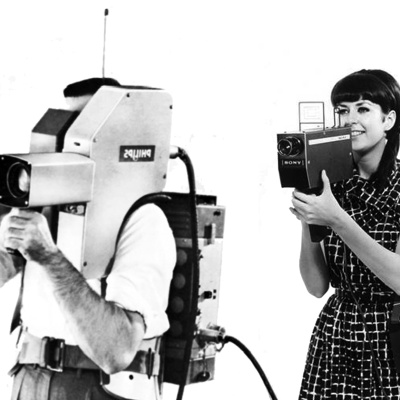

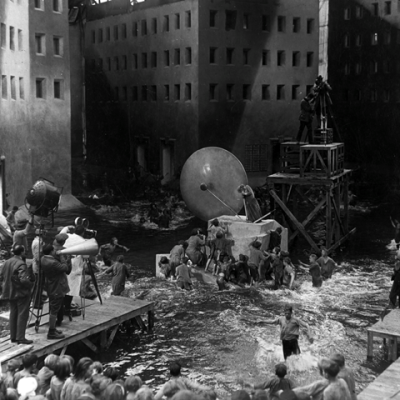

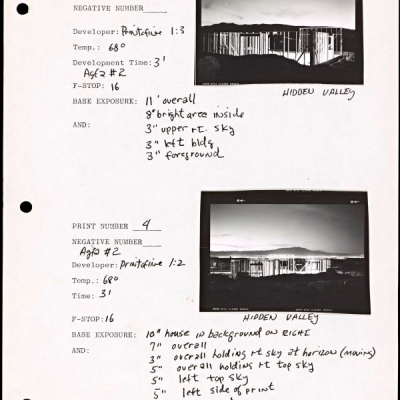

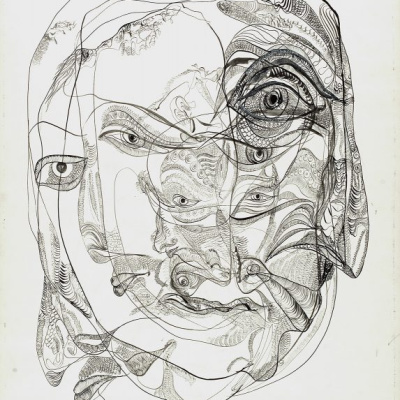

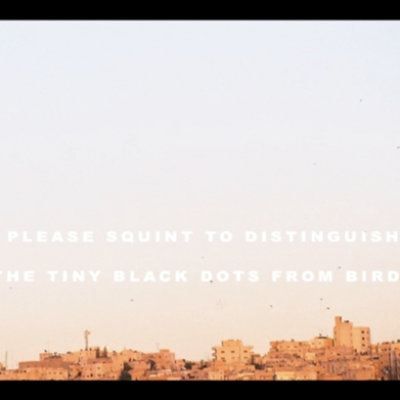

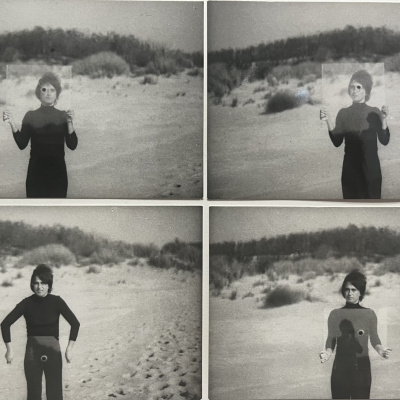

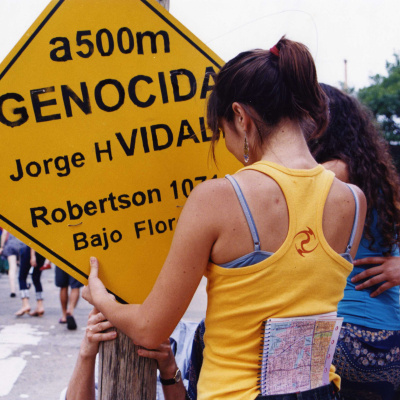

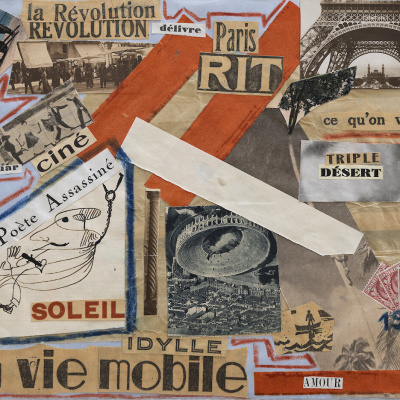

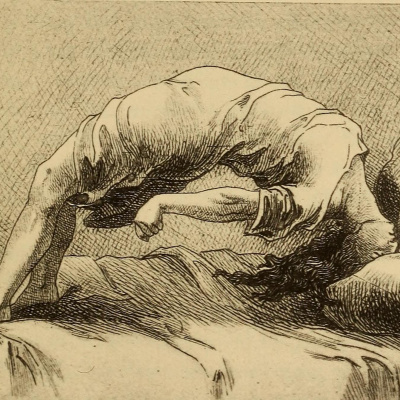

To describe the African diaspora following the journey on the slave ship, Glissant draws the image of a living fibril. These journeys caused a violent severance, an erasure of a world, however, an incomplete severance. This incompleteness made possible the forming of spaces within the brutality of the plantations, within which there was room for rituals, relationships to ancestors, rhizomatic connections between the enslaved and forms of autonomy. For Glissant, such spaces included the creole gardens. Similar to the image of a living fibril, Ariella Azoulay describes a ‘’photograph-to-be’’; an immaterial construct that prefigures and conditions the closing and opening of the shutter, as well as the violence which accompanies its operation. The work begins by tracing the Creole gardens, which for a long time escaped the Western gaze and the brutality of representations otherwise seen, for example, in the depiction of the cottages of the enslaved. This violence persists today, through representing in research sacred and secret traditions and plants which exist in these gardens. If we consider the photograph-to-be as an ideological apparatus, accompanying violence and contributing to it, and ideology, as Althusser puts it, as omnipresent. If we consider that ‘’the eternity of the subconscious is not unrelated to the eternity of ideology’’, and if we believe in the non-finality and reversibility of the shutter as well as its reversibility, it is possible to compare the shutter to the ‘’setting’’ in a psychoanalytic process. Using Jane Rendall’s site-writing method, self-portraits are taken in an attempt to remove the ‘other’ who controls the shutter, and to uncover through self-portraits the politics of one’s own body in representation. Photographs were taken, written about, and retaken, uncovering a tension between the body and the lens, discovering the boundaries of a woman’s body in representation. These boundaries are then crossed to display parts of the research, moving so close to the body that its nakedness becomes undecipherable, freeing the body from the gaze while reminding and hinting at, but not analysing or dissecting the Creole Gardens.